For decades, organizational silos have been a rational, if frustrating, feature of corporate design. Despite being seen as a source of dysfunction, the deliberate structure prioritizes stability over innovation to protect core operations. However, the economic foundation of that trade-off is now starting to crack. Now, a new wave of agentic AI is making it cost-effective and accessible to connect disparate business functions. But it's also challenging the very assumptions that still give rise to these silos today.

To learn more, we spoke with Subramanian Iyer, PhD, Scientific Advisor and Chief AI Officer at Silicogenix, a biotech startup using AI to accelerate small-molecule drug design for rare cancers. A senior AI and data science executive with over 20 years of experience creating high-impact AI systems, Iyer has delivered multi-billion-dollar business impact at major corporations, including Target, Albertsons, and Goldman Sachs. Today, his perspective reframes the conventional wisdom about corporate dysfunction. Iyer believes a fundamental change in corporate design isn't just possible—it's inevitable.

"Corporate design isn't dysfunctional at all. Dysfunction is a feature, not a bug. Corporations were designed to ensure they're always operational and profitable. It’s paramount to ensure business continuity rather than to be on the vanguard, and innovating constantly," Iyer says. Initially, the logic behind the siloed design was rooted in local optimization, he explains.

A model popularized by Henry Ford's assembly line, the historical difficulty of company-wide coordination led to departments operating with different abstractions of the business.

The resulting structure encourages local goal optimization without a clear view of end-to-end profitability, Iyer explains. For example, a supply chain manager's primary job is to keep shelves stocked, while a finance manager's focus is on maximizing ROI. Usually, these separate functions connect "only when there is a crisis." Unfortunately, that system can also produce ill-considered incentives, he says.

Costly crisis: Take, for instance, the "use-it-or-lose-it" budgeting phenomenon. Here, a manager is motivated to spend their remaining travel budget on a retreat just to avoid a cut the following year. "Look at what happened after the pandemic," Iyer says. "You had merchants acting on the assumption that the world would keep growing at 15% every year, while the people running clearance sales were celebrating the fact that their own 'empire' had grown. But nobody was looking at it end-to-end and asking whether those local, optimal decisions made sense for the full business."

Bookstore ideal: As a caveat, Iyer points out the difference for a mom-and-pop bookstore. "The owner has a complete understanding of everything: what books he’s ordering, where he’s ordering from, what’s selling, what’s not, and the cost of reverse logistics. The whole thing. In a 10,000-person business, you have extreme levels of specialization, and no one is really thinking about end-to-end profitability."

Since corporate inertia makes internal reform challenging, Iyer says external pressures will instead drive change. Eventually, these "forcing functions" will come from two directions: new, tech-native competitors built around an integrated model, and outside investors who acquire and consolidate fragmented industries by injecting technology—a strategy already being deployed in sectors like accounting.

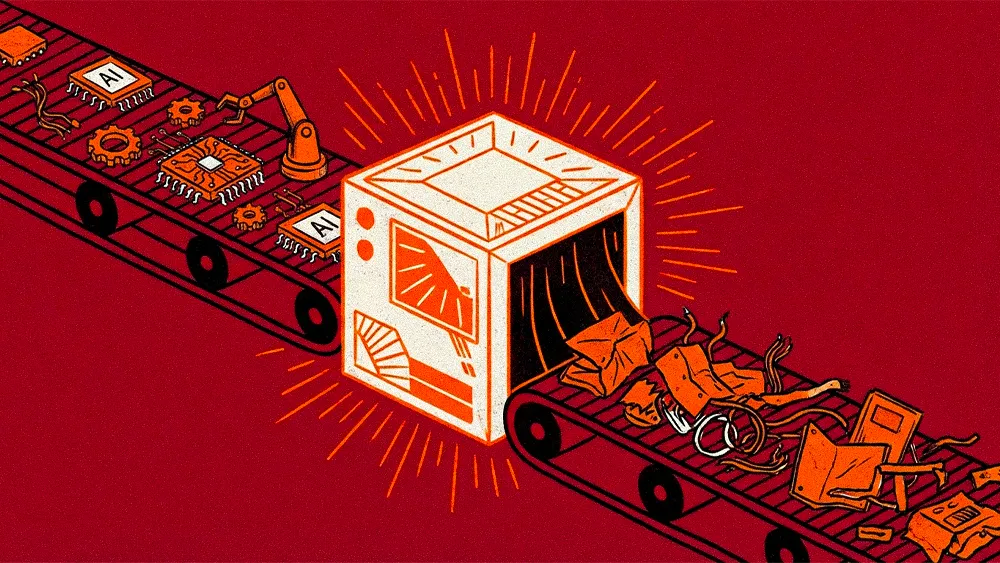

For Iyer, the technological key for this disruption is agentic AI. Acting as an intelligent, flexible layer—a central nervous system—on top of existing enterprise software from vendors who are already developing these AI agent platforms, agents enable different functions to communicate and make integrated decisions in real time.

Flavor of reason: So, what makes this model poised to succeed where past attempts at enterprise integration failed? "In the past, all logic had to be rules-driven. You couldn’t create logic that could teach itself or improve over time. Machine learning, however, can provide enough of a flavor of reasoning that you don’t need such extreme, rules-based logic," improving both performance and transparency.

The technological change could even trigger a radical restructuring of traditional org charts, Iyer says. Once AI makes integrated decisions across procurement, marketing, and finance, the old model could become obsolete.

Mirroring the machine: Some companies are already reorganizing to sharpen their AI focus. "When you rethink the company as an AI-first company, you can build solutions that cut across these organizations. The goal is to build your organization to reflect those solutions, so the technology and the organizational structure mirror each other. You avoid the common pitfall of starting with a rigid structure and trying to shoehorn AI into it."

Business of bananas: Eventually, Iyer said, companies will face significant pressure to reorganize their human talent into small, cross-functional teams built around end-to-end profitability, recreating the holistic ownership of the small bookstore owner, but at enterprise scale."So you create a banana team. The job of the banana team is to make sure that they're profitable on bananas. It is not their job to maximize banana sales. It is not their job to minimize the cost of bananas. It is their job to maximize the profitability of bananas."

Ultimately, the real disruption will begin when the market starts offering turnkey, vertical-specific solutions, Iyer concludes. "I don’t think we’re there yet. But as and when we get there, that will be the tipping point in many, many different industries." Here, he also adds a dose of realism: "I’m not entirely sold that this is imminent. Due to the software's quality, I don’t think it’s there yet. Maybe it’s not GPT-5, maybe it’s GPT-21, but we are going to get to a place where the quality of decision-making is highly superior."

Once the technology matures, however, the first company to successfully implement this integrated model could trigger an industry-wide arms race. "Somewhere in maybe inning three or inning four of the coming wave, a lot of these horizontal solutions will be created for the verticals. For example, if you’re running a healthcare business, you’ll get a lot of the necessary machine learning models out of the box. Then, rather than just getting an MLOps platform and building all the models yourself, you can customize them. And that will create a wave of highly scalable, smaller businesses which will be able to move much more nimbly."