For years, the tech industry has been guided by the belief that humans will adapt to whatever tools they are given. In the age of AI, that belief now carries significant and unforeseen operational risks. The reason is scale. With artificial intelligence, a single algorithmic error no longer stays local. It can propagate globally in an instant, revealing a gap between the technology's power and the corporate safety practices meant to govern it.

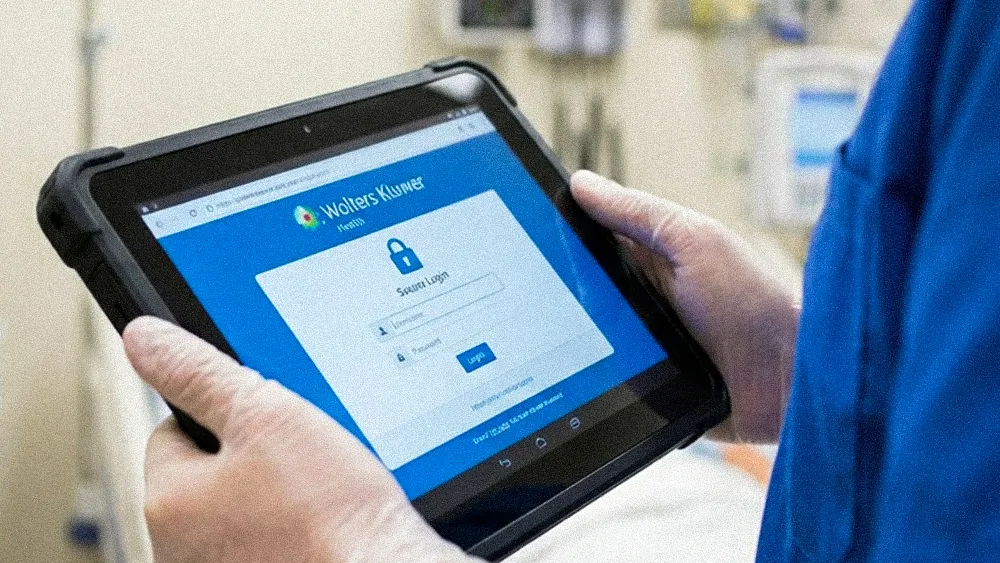

We spoke with Ayoola Lawal, Managing Partner of LRA Consulting and an experienced global strategist. While his career has focused on connecting global markets and advising on corporate leadership, his expertise also extends deep into a fundamental challenge facing the tech industry. As a PhD Candidate in Human Factors, Occupational Safety & Health with a research focus on AI and Automation, Lawal believes AI's scale calls for leaders to revisit an underutilized discipline.

"Human factor engineering has always existed. AI is what makes it impossible to ignore, because the cost of failure now scales faster than organizations can absorb," he says. Recent analysis confirms that many AI companies fail to meet global standards, a challenge highlighted in major initiatives like the International AI Safety Report. As a result, the industry's "fastest-to-market" mantra is being replaced by human-centered design, which has moved from an ethical add-on to a core economic reality.

Design for messy humans: Human factor engineering encourages designers and leaders to account for the often-messy reality of how people interact with systems. "It's about designing tools, systems, and environments to improve efficiency, safety, and reliability. The ultimate goal is to design for how humans actually behave, not how we wish they would behave," Lawal explains.

Like other industries and technologies before it, AI is demonstrating that safety inflection points are often reached following repeated failures. Lawal says aviation, medicine, and finance are strong examples of this. "I call it an autopsy moment. When we look at the aviation industry, they figure it out in terms of safety after enough crashes. In the financial market, after enough market failures." He advises leaders to resist the impulse to respond to failures by purchasing new tools. The fix, he says, begins not with technology, but with culture.

Practice versus performance: "A company can claim its safety culture is great, but that is often just performing safety, not practicing it," Lawal points out. He offers the automobile industry as the perfect analogy. Cars have safety features like seatbelts and airbags built in, but the main reason most crashes are avoided is that we've built a culture where drivers stop for red lights. "You do that even when people are not there. When people are not watching, you still don't run past the red light. That is the culture."

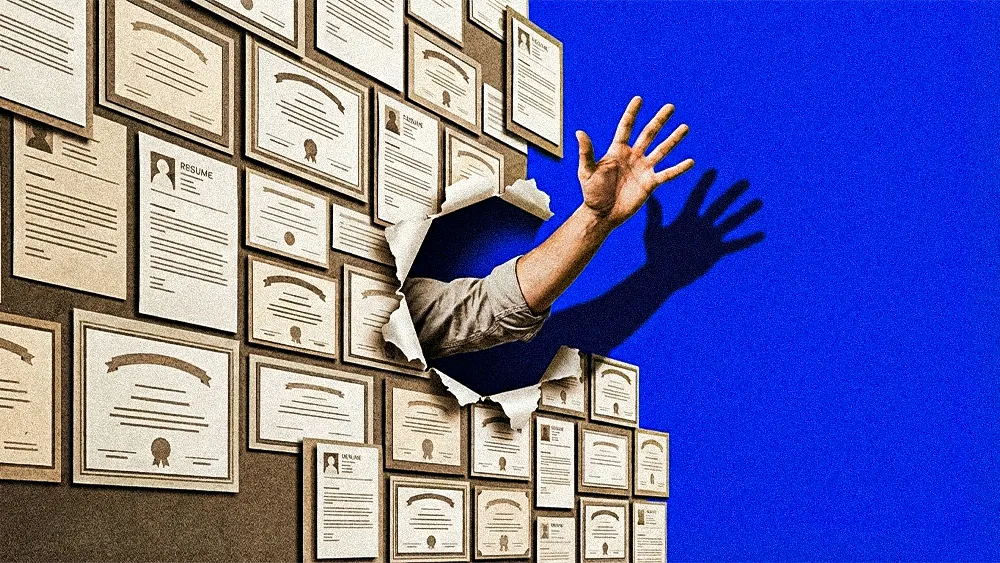

Visibility before control: In an era where executive AI literacy is a prerequisite for effective governance, Lawal argues that the dashboards and high-level metrics leaders so often rely on are insufficient. "Once a system is deployed, the responsibility for the decisions it makes falls to the executives. How do you gather what you don't see? How do you govern what you don't understand?" True executive visibility, he says, is "about having access to the actual decision audit trail."

Knowledge over rank: Lawal advocates for a kill switch that values expertise over hierarchy. "If the system goes wrong at two in the morning, you don't have to wait for a stand-up meeting the next day at maybe seven AM to switch it off," he says. This is formally known as an inverted authority structure. It gives the person with the most system knowledge, not the highest rank, the power to intervene.

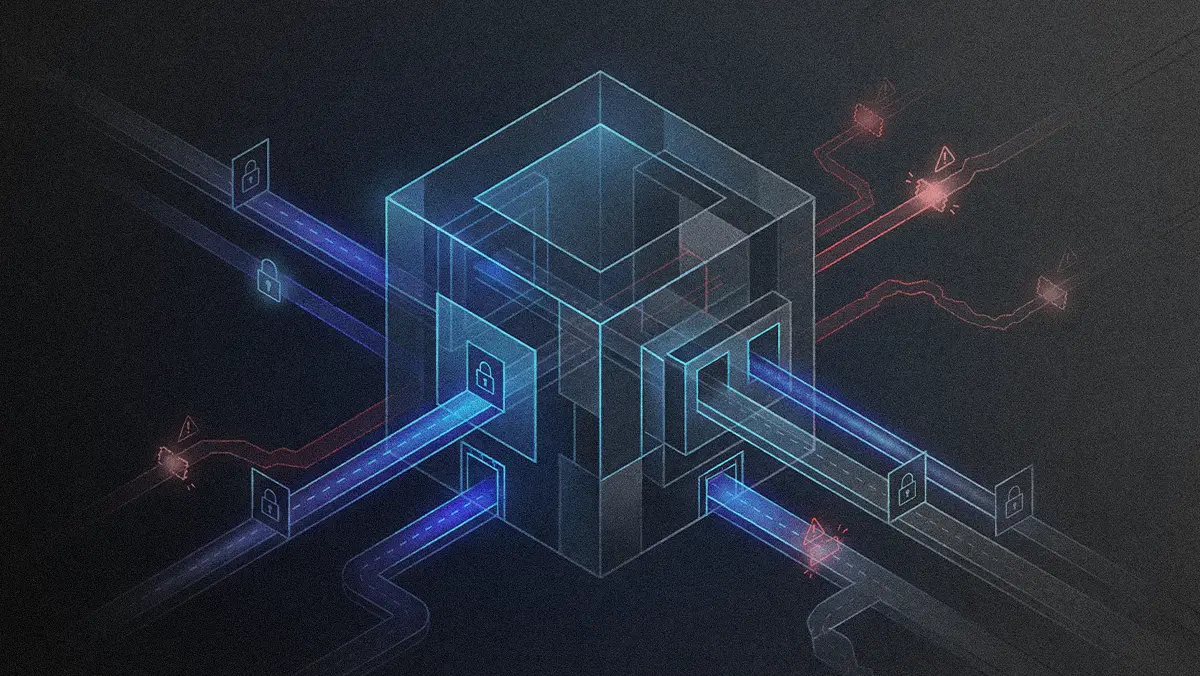

The rationale for adopting these principles is grounded in a convergence of economic, regulatory, and reputational pressures. Lawal calls it the ER-squared framework, and it creates a compelling case for a human-centered approach.

An expensive trio: Economic pressure comes as liability exposure, which "is growing faster than the capabilities of organizations," Lawal asserts. Regulatory pressure is materializing in policies like the EU AI Act, with governments moving from voluntary compliance to penalties for noncompliance and demand for interoperability across frameworks. And the reputational damage can be severe. "Trust erosion is now monetized and measured in quarterly earnings."

These factors, Lawal says, have always existed, but AI makes ignoring them economically and reputationally untenable. "The successful organizations have always been able to be above that curve. Most are just dragging along, but now it's difficult to escape."

He sees this re-evaluation of priorities as part of a recurring pattern, noting that every high-consequence industry experiences it after a period of velocity-driven growth. As the old way of doing business becomes unsustainable, Lawal cautions against leaving security out of the business equation. "If any organization takes safety for granted now, it does so at its own peril."