For decades, hardware sent into space was rigid and purpose-built, its function singular and its design constrained by the harsh physics of size, weight, and power. But that era is giving way to something new: general-purpose data centers operating in orbit. The change creates a rare greenfield opportunity for the industry to define standards, interoperability, and architectural principles from scratch, a clean slate not seen since the early internet. And unlike the patchwork of proprietary systems that grew out of terrestrial data centers, orbit gives the industry a moment to get it right from the start.

Travis Steele, Chief Architect, Air Force and Space Force at Red Hat, brings a long track record of delivering results across complex, high stakes environments, from General Dynamics to Hertz. He has been deeply involved in shaping the emerging model for orbital compute, and his view is clear: The decisions made over the next few years will set the long term blueprint for how compute, storage, and AI function in orbit, and the window to influence that foundation is already narrowing.

"This is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to shape the next greenfield technology arena. If you want to influence how an orbital data center works for you, you need to be involved now," says Steele. The greenfield opportunity offers a chance to apply hard lessons from terrestrial infrastructure. On Earth, data centers evolved layer by layer, forcing every new capability to fit inside environments that were already inflexible. Over time, this created a maze of proprietary systems, uneven compatibility, and vendors that did not always play well together.

Avoiding a space sequel: Steele says orbit gives the industry a chance to avoid repeating that history by setting standards early and aligning them with the needs of the future space economy. As he puts it, "it's very, very important that we have a set of open standards that are modular, where interoperability is a first-class citizen. We absolutely have to adapt and leverage the regulations that are already in place across these different industries."

No roadside assistance: Space leaves no room for improvisation once hardware is deployed. Components cannot be swapped, patched, or reconfigured as they can on Earth, making modular design and interoperability essential. They determine whether an orbital platform stays usable for years or becomes stranded the moment technology moves on. "Unlike a terrestrial data center, we can't drive a truck and back it up into space to switch out components," Steele explains. "So the priority is a standards layer that encourages modularity and allows every system to interact without barriers."

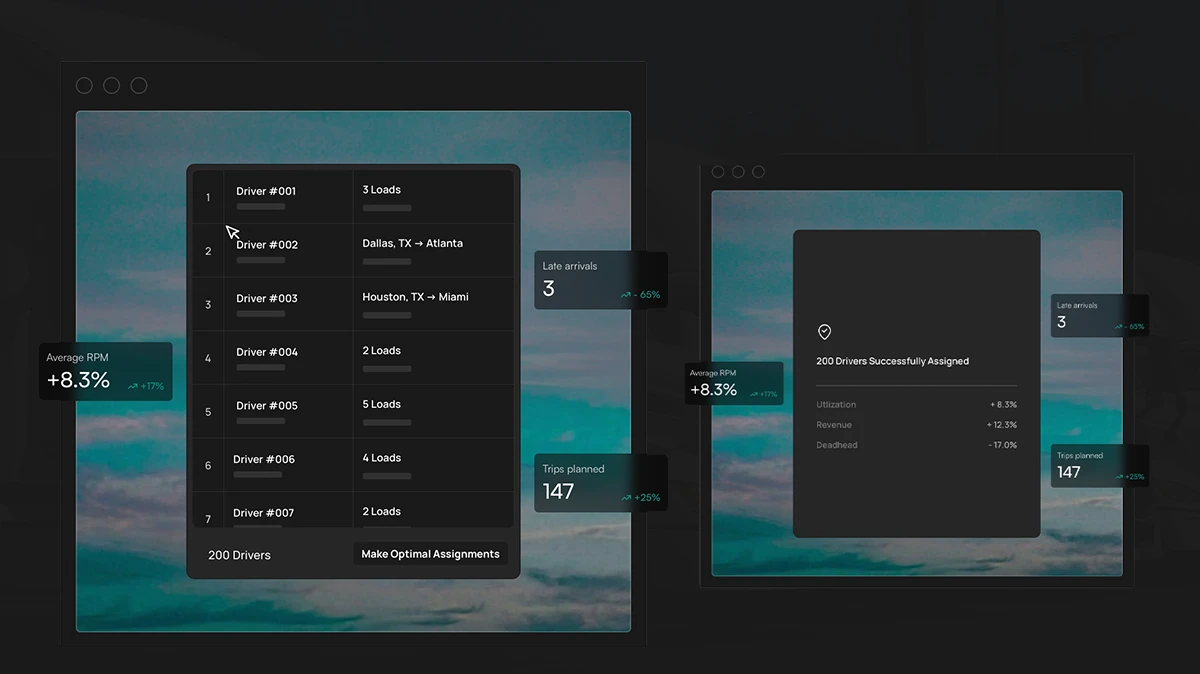

Proponents say the move toward orbital computing is possible because two fundamental barriers are beginning to fall: the prohibitive cost of reaching orbit and the physical limitations of hardware in a resource-constrained environment. Steele explains that innovation is increasingly driven by the intelligent application of software, with breakthroughs matured in the open-source community providing the ability to overcome the severe constraints of space. Combined with a revolution in launch economics, many of the old rules of space-based hardware are being rewritten. The technology is already being tested, with early platforms now operational on the International Space Station.

Linked among the stars: "What SpaceX and Starlink have demonstrated is a path to democratize putting payload consistently into space. In the past, the number of launches was quantified over multiple years; now, launches happen almost every day. Because of these advancements, getting a payload to space in a cheaper, more economical way is a reality," says Steele.

But the opportunity comes with a timeline for industry influence, driven by a multi-stage roadmap that is already underway. The industry is poised to move from today’s prototypes to the first free-flying orbital data centers within the next couple of years. Then, as the ISS is decommissioned by the end of this decade, a new generation of commercial space stations is expected to emerge, incorporating their own data center modules.

The concrete is setting: To help guide this future toward being open, Steele says that a community of interest must form now to define requirements for these open, modular architectures. From his perspective, early adopters who fail to get involved now risk being forced to live with the standards others create. "As momentum builds between 2026 and the end of this decade, there won't be an opportunity to influence these architectures. At some point, decisions get locked down. You have to go through extensive testing to be flight-ready, so we need to get those requirements, goals, and desires into the pipeline now."

The combination of AI, real-time processing, and orbital compute could also signal a fundamental change in how future scientific and commercial value will be created. The goal is a future where the convergence of AI and data enables true sovereign AI, with information wholly produced in space without any Earth dependence—a reality that, in Steele's view, is approaching much faster than previously thought.

Steele emphasizes that the promise of this evolution is in the tangible benefits that could follow, with the potential to touch every person on Earth by unlocking capabilities that can only be fully realized in the unique environment of microgravity. "The impact will not stay in orbit," he concludes. "It will show up in medicine, in safety, and in everyday services that get better because space finally becomes part of the compute fabric."